By Thuita Gatero, Managing Editor, Africa Digest News. He specializes in conversations around data centers, AI, cloud infrastructure, and energy.

Something about the new AMD–OpenAI deal does not smell right. On the surface, it looks exciting: AMD, one of the biggest chipmakers, partners with OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT. At the same time, OpenAI already has a huge relationship with NVIDIA, its main supplier of powerful AI chips. So now, we have OpenAI working with both AMD and NVIDIA, two companies that normally compete. That alone raises eyebrows.

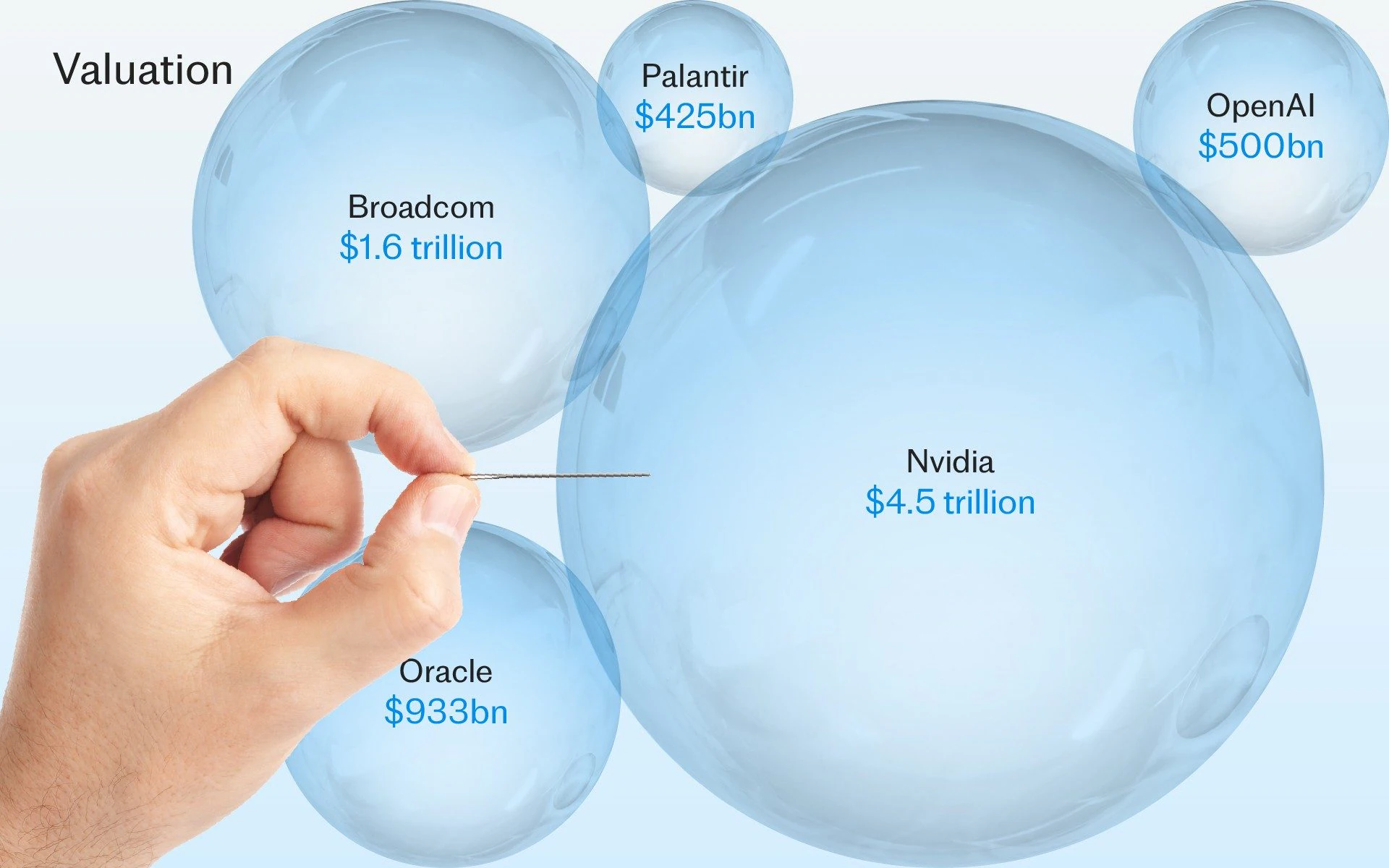

Here’s where it gets strange. NVIDIA is investing about $10 billion for every gigawatt of computing power OpenAI builds, roughly a total of $100 billion by 2030. That money flows into OpenAI, which then uses it to buy more NVIDIA chips. Meanwhile, OpenAI also signs a deal with AMD to buy their chips. AMD’s stock price goes up because investors think “OpenAI is betting on them.” But since OpenAI also owns a piece of AMD, and NVIDIA owns part of OpenAI, when AMD’s stock rises, everyone’s value goes up together. It’s like three people taking turns inflating each other’s balloons with the same air.

AMD has agreed to give up 10% of its company to OpenAI as part of the deal. For a company whose profit margin (11.3%) is much smaller than NVIDIA’s 56%, that is a big sacrifice. So why would AMD do it? The simple answer: branding. It is like paying for celebrity endorsement. When the headline reads, “OpenAI bets big on AMD,” investors get excited, and the stock price climbs. It’s a smart PR move but not necessarily a profitable one.

NVIDIA, on the other hand, is in a completely different league. Its gross margin (72%) is nearly double AMD’s (39.8%), meaning NVIDIA keeps far more of every dollar it earns. You can think of NVIDIA as the luxury brand of chips, selling expensive “gold-plated shovels” during the AI gold rush. AMD, meanwhile, is the affordable alternative trying to get noticed. In this ecosystem, NVIDIA is the casino owner, OpenAI is the star attraction, and AMD is paying for a seat at the table.

But what worries analysts is the circular nature of these deals. Money goes from NVIDIA to OpenAI, from OpenAI to AMD, and then back into the market, raising valuations without necessarily creating real profit. It’s like a group of friends taking out loans to buy each other’s products, all claiming they’re getting richer, even though the total money in the group never increases. That is not innovation, that’s a valuation loop.

We have seen this movie before. In 1929, the stock market crashed 17% in a single month. By 1930, it was down 33%. In 1931, it had fallen 50%, and by 1932, it had lost 80% of its peak value. That era, the Great Depression, started with exactly this kind of euphoria. People believed prices could only go up. Banks lent freely, companies traded shares with each other, and “easy money” created the illusion of unstoppable growth.

Fast forward to today: the Buffett Indicator, a ratio comparing total stock market value to national GDP sits around 217%. Historically, anything above 120% means the market is overheated. In plain English, that means the stock market is worth twice as much as the real economy produces. To justify current AI stock prices, the industry would need to make $2 trillion in annual revenue by 2030, but current projections show only $1.2 trillion. That’s a 40% shortfall, a hole you can’t fill with excitement alone.

What comes next is often predictable. When fear peaks, investors with cash buy cheap. Then FOMO (fear of missing out) sets in. Prices rise, people borrow to buy more, euphoria spreads, and soon stocks are valued more on hope than earnings. That’s the “mania” phase, the same one that preceded the dot-com crash in 2000 and the housing bubble in 2008.

Here’s what’s really happening: imagine AI as the next industrial revolution. Everyone knows it’s the future, but before it changes your daily life, someone has to build the factories, train the workers, and connect the power. In today’s case, those “factories” are massive data centers, those “workers” are algorithms trained on trillions of data points, and that “power” is literal, electricity to keep everything running.

Now, building all that does not happen overnight. It’s like wanting a harvest the day after you plant the seeds. Investors are throwing money at AI companies hoping for quick returns, but the real payoff is still a few years away. And while all that building happens, something interesting occurs in the background, the world’s financial plumbing has to adjust.

Central banks, the institutions that control how much money flows through the economy may have to print more money to keep up with the cost of this new infrastructure. That can mean lower interest rates again, which sounds good for borrowing but can also inflate asset prices and widen inequality. Meanwhile, millions of workers whose jobs are being replaced or reshaped by AI won’t immediately find new ones. There is always a lag,, just like when tractors replaced farmhands or when computers replaced typists.

So when we say “AI will change the world, but not as fast as investors expect,” it’s not just about technology. It is about time, infrastructure, and adjustment. We are witnessing the setup phase of a transformation, not the payday moment. The smart investors and policymakers know that the next few years are about patience, not panic.

So yes, the short-term story is growth. But the long-term question is whether this growth is earned or engineered. And right now, too much of it looks engineered, a financial circle that only works as long as everyone believes it will. The last time markets ran on belief instead of balance sheets, it didn’t end well.

Leave a Reply